Blog Posts From The Glorious Future: The Breaking Of The Man With The Iron Heart

The most radical reforms of the Great Redo were reserved for America's immigration policy

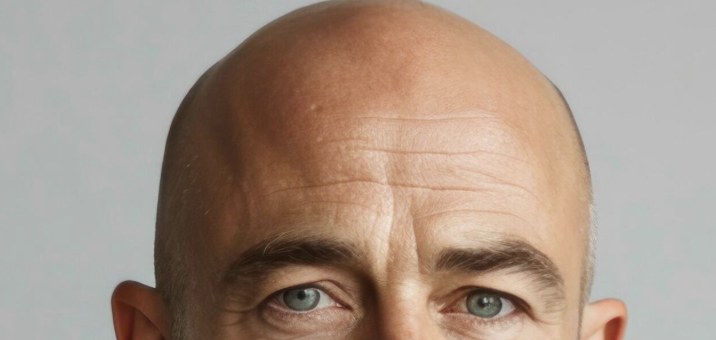

There was a particularly nasty one, with a nasty disposition and a nasty scowl and the nasty tattoos to match, who refused to break. Until one day, he did.

His name was Geoffrey, though he refused to answer to his given name. He wanted to be called Reinhard, in honor of Reinhard Heydrich, perhaps the most violent and evil member of the Nazi Party known as the Butcher of Prague. Reinhard, Geoffrey said, had done nothing wrong. He got a bad rap in the years after the war because “the victors write history.” Geoffrey said he admired Heydrich’s resilience, and his refusal to allow his enemies to escape justice. “He did what needed to be done,” Geoffrey said of Heyrdrich, whose nickname was Man With The Iron Heart, and who oversaw myriad executions of civilians during the Nazi occupation of Prague. “He is a hero of humanity. He wanted to save the world.”

Geoffrey was a member of America’s secret police in the Bad Times. Some back then called it ICE, but it took many forms: Armed vigilantes marauding through communities of color and the downtowns of major American cities, rounding up anyone and everyone who looked to them like undocumented immigrants. Geoffrey had participated in the first and second insurrection. In between those two uprisings, he bounced between positions for border patrol and Immigrations and Customs Enforcement, a rogue entity that had declared itself a quasi-government not subject to the law of the United States. No one in power challenged that arrangement because ICE agents and those cosplaying as ICE agents would disappear them, or kill them and display their bodies as a warning to the regime’s opposition.

I recall one such display from my college years: A state lawmaker in New Mexico placed on a busy street holding his head and the head of his dog, a black lab. That state senator had cast the deciding vote to launch a formal investigation of secret police agents who had arrested Albuquerque city council members and the mayor and were essentially running the city themselves. A sly smile slid across Geoffrey’s face when I recalled that story. I asked him if he thought that massacre was funny. “Yes,” he said. “I do.”

Geoffrey was among the ten percent of secret police who chose imprisonment over working at the Immigration Assistance Centers all along the southern border. The Great Redo national security reforms included hundreds of pages of proposals for deradicalizing those in local police departments, border patrol, ICE, National Guard, and other agencies and institutions that had long ago rejected federal government oversight. These people – men, mostly – were a government within a government and would do what they wanted to whomever they wanted with no repercussions. That ended with the ushering in of the Redo reforms. ICE was abolished within days. So was Border Patrol and the Department of Homeland Security, a relic of the War on Terror that had been turned against the American populace.

Every single person even loosely associated with these agencies was arrested and housed in the concentration camps they had built for migrants in the Bad Times. Most were shipped to the camp built in the Florida swamps, where hundreds of migrants died with no explanation from authorities (the former governor of Florida was arrested at the Miami airport the day after the president’s election; he, like so many others, had planned on fleeing to Russia). There was room in those camps because they had been emptied out within 48 hours of the Redo taking effect, and every migrant kept in the inhumane camp conditions was housed and cared for by the federal government. They would later be awarded reparations for the horrors they had endured at the hands of the American government. The idea was that these migrant families would never again want for money or food or healthcare. We would take good care of them after they had been treated as less than human for so many years. Geoffrey once spat on the ground when I mentioned the reparations in passing.

Geoffrey was one of my clients in those early days. I worked with sixteen former members of the country’s secret police, all of whom had been convicted of crimes against humanity in trials conducted by a special Great Redo truth and reconciliation commission. Fifteen of my clients cried during the trials and begged for mercy and said they had only followed orders, that it was not their fault. They had no choice, they said through tears. There were no good jobs in the Bad Times, they said, and the secret police kept a roof over their heads. Please, they begged, give us another chance.

Geoffrey did not cry. In fact, he smirked and told a prosecutor that he would do it all again if he had the chance. He told me stories in those early days after his conviction. He told me about the time he and a police buddy stormed a hospital one morning and arrested a six-year-old boy being treated for lukemia. The boy refused to come with them and a nurse said she would not let them take the kid, who had entered the country without proper documentation as a toddler. Geoffrey said his colleague flashed a gun at the boy and laughed as the kid peed his pants. He turned and shot the nurse in the knee when she punched him in the back. They dragged the boy to a nearby camp, where he died six weeks later. Then there was the story of the time Geoffrey and his partner forced a grandmother from El Salvador to choose which of her two grandchildren would be taken to the camps. They couldn’t tell who was who, and no one in the house would help them identify the pre-teen girl who had violated U.S. law when she entered the country at a secret entry point controlled by Mexican gangs. “So we said, OK then grandma, choose,” Geoffrey recalled. “She’s crying and screaming and vomiting and asking god to strike us down and all that shit. We refused to leave until she chose. It took an hour.”

“Eventually,” Geoffrey said, “she understood we were more powerful than god. It just took her a while.” Maybe he really was the reincarnation of Reinhard Heydrich, the Man With The Iron Heart.

I was among the hundreds of federal workers trained and deployed to de-radicalize those who had served in the secret police during the Bad Times. De-radicalization was – and still is – a key plank in the Redo agenda, which sought to drain the country of the right-wing extremism that had degraded our democracy and made the courts and Congress powerless to stop our slide into authoritarianism using traditional methods. In re-radicalizing members of the secret police, the hope was that most of them could be rehabilitated through service to the very people they persecuted in a former life. The Great Redo, after all, is about justice above all else, about rejecting the violent peace that had defined the US for generations and delivering justice to those who had been trampled amid the fascist excesses of the Bad Times. No people deserved justice more swiftly than the immigrants who had been treated worse than animals in keeping with national policy.

One of the more controversial planks of the Great Redo agenda was the president’s insistence that states that had been home to the country’s migrant concentration camps had to have at least some migrants in their state legislatures. One of the great failings of post-Civil War Reconstruction, the president told her staffers and administration officials, was the federal government’s premature withdrawal of requirements for formerly enslaved people to serve in legislative bodies. This, she believed, needed to be a long-term feature, not a temporary arrangement. So all fourteen states that held concentration camps in the Bad Times – mostly in the South and Midwest – were mandated to have fifteen percent of their legislature composed of migrants who had been jailed in the camps. These people were appointed by Redo boards tasked with democratizing the South. They would receive around-the-block security and could serve in the legislature for as long as they wanted.

Critics called it a humiliation. The president in private said she was glad they were humiliated, that they needed to feel shame for what they had done. “We sorely miss shame,” she said. “It serves a function in a working society.”

When this was leaked to the press, the president denied it and blamed the enemies of the Great Redo.

‘I Won’t Debase Myself’

About nine in ten former secret police chose to work full time at the Immigration Assistance Centers, where, under close supervision, they would register incoming migrants as legal U.S. citizens, ensure they were provided with proper care – including meals, clothing, and transportation to apartments built for migrants fleeing poverty and violence – and check in with those families once a week to make sure all their needs were being met. The former secret police – people who used to torture and kill migrants at the southern border, often for fun – were forced to become caretakers for migrants and their families. There was one former secret police – a woman who worked at a camp in eastern Idaho – who was tasked with taking an immigrant child to the doctor, getting her tested for gluten allergy, and then buying gluten-free food for the girl over the next few months. This woman was monitored closely throughout, spending no time alone with the little girl.

Like all the rehabilitating police, she was at first resentful of her sentence: Taking care of the humans she had tormented for so long. She once told me it was cruel and unusual to force former secret police to tend to the needs of immigrants. I reminded her it was in fact a choice, and that she could spend her sentence inside a former concentration camp if she would prefer. “Say the word and you’ll be in the camp tomorrow, I promise,” I told her. She sneered and walked away.

I spent the following weeks documenting the dissipation of this woman’s resentment and hostility. She began to speak with the little girl and her family, some of whom could hold a conversation in English. Then one day, shortly before Christmas, the former secret police member came down with something and was taken to a local hospital for an IV and evaluation. A nurse called me that afternoon and told me the former police had woken from a nap in a frenzy. She asked to speak with me.

“Today is Tuesday, remember to tell my replacement to get the gluten free stuff, especially the snacks,” she said, offering to list the little girl’s preferred snacks if I would jot them down. I could sense the warmth in her voice. She cared for this little girl. This former secret police had broken.

It wasn’t so easy for Geoffrey. He chose to be imprisoned in the Florida swamp camp after his trial and had expressed no interest whatsoever in transitioning to an Immigration Assistance Center. “I won’t debase myself like that,” he told me once while absentmindedly rubbing the iron cross tattoo on his right forearm.

So Geoffrey lingered in the camp-turned-prison for months and months. I got a report one summer morning that he had been put in solitary confinement, a punishment we had only reserved for the worst of the worst. Apparently he had maimed two inmates who had agreed to serve at an Immigration Assistance Center in southern Florida. Both were in the hospital for days after Geoffrey’s attack, which involved a pair of scissors he had stolen from an office in the camp. “I was saving that for the guards but had to use it on the sellouts,” he told me later.

Geoffrey spent the better part of a month in solitary because every time he was evaluated, he attacked another camp guard. He was reportedly a biter.

I had had a lot of trouble getting in touch with Geoffrey’s family and friends. Doing deep background wasn’t necessary for every former secret police, nor was it a mandatory part of the job. But like so many who had signed up for our reform government in the early days of the Redo, I was ready and willing to do whatever it took to make a difference, especially in re-radicalizing what was essentially a homegrown terrorist cult that had never faced any pushback from lawmakers or the courts. They needed to know what justice felt like, and without serving those they had wronged, I didn’t believe they would ever achieve that. Rotting away in a former concentration camp was only going to make these men more monstrous. Without re-radicalization – reprogramming, we used to call it – there was no path to these people being free.

It was around the time Geoffrey finally got out of solitary that one of his ex-wives got in touch with me and only agreed to meet in an abandoned lot miles from her home. Geoffrey, she explained, was a psycho who kept tabs on his exes – all three of them. His six children, she said, hardly ever crossed his mind beyond the desire to “populate the earth with the Aryan race.”

We met one evening in that abandoned lot. Her name was Claudia, and for the entire forty-minute conversation, she refused to make eye contact. I could feel her fear. Claudia’s hands trembled as she told me about Geoffrey’s past, which had been tough to track down thanks to secret police officials burning the files of their agents on election night. Claudia said Geoffrey had not always been this way. He was once a normal if reserved guy who coached youth basketball and taught elementary school science. He had written a couple science fiction books that never quite reached publication. Geoffrey was a big Star Wars fan, spending an inordinate amount of time arguing and commiserating with fellow Star Wars fans on social media. Claudia pulled up a photo of Geoffrey dressed as C3PO for a Halloween party. His face was adorned with a smile; it was almost surreal to see. I had only ever seen a scowl.

Geoffrey’s descent into radicalization, Claudia said, began with a car accident. He was driving home one night from a basketball practice with his eight-year-old daughter, Marlene, when a Honda SUV blew through a stop sign and smashed into his hatchback Toyota. Marlene and Geoffrey were rushed to the hospital and when Geoffrey came to the next morning, he was told Marlene had succumbed to massive internal injuries.

When Geoffrey later learned that the Honda SUV had been driven by an immigrant in the US with green card status, a darkness slipped over him, Claudia said. He instantly became a different person: He began obsessively lifting weights, he experimented with steroids, he shaved his head, he got nazi tattoo after nazi tattoo, he shunned science fiction and read nothing but fascist literature and blogs that had been protected by the First Amendment before the Redo reforms banned that particular societal poison. “You could kinda see his hate grow a little bit every day,” Claudia told me. “He was obsessed with the idea that immigration had cost him his daughter. Without immigration, she would still be around. That was his thinking anyway.”

Geoffrey deliberately sunk himself into fascist social media networks that had ruined so many families and friendships in the Bad Times. Eventually, Geoffrey was insistent that the Holocaust did not happen, black Americans were better off under chattel slavery, and the American insurrections had been justified, even necessary to stop Jewish bankers from taking over the country. Claudia said the slightest pushback to these conspiracy theories would illicit terrifying outbursts from Geoffrey, who once threw a kitchen chair at Claudia when she said she believed the moon landing had happened. He was threatened to kill her and eat her for dinner.

A day later, I tracked down Geoffrey’s oldest living child, a young man named David, who confirmed Claudia’s story. David said he and his younger brother had been forbidden to talk with their black neighbors or listen to rap or hip hop. Their father showed them social media videos of black teenagers brutally beating white kids on school buses and in school hallways. “They can’t help it,” Geoffrey would tell his sons. “It’s in their nature to be violent.” Geoffrey had barred them from playing basketball because, as he told it, basketball was a “black sport” that had been taken over by a cabal of radical black activists.

It was around this time that Geoffrey asked to meet with me. I feared he had learned about my conversations with his son and his ex-wife. But no. He was ready to take the deal and work at an Immigration Assistance Center. The two prisoners he had beaten unconscious had powerful allies inside the Florida prison, and they were primed to make Geoffrey pay for what he had done to them. “They’re going to castrate me,” he said during our meeting. “I need to get out.”

I had Geoffrey transferred to the busiest Immigration Service Center in the country in Brownsville, Texas, right next to the Mexican border. Even with three times as many workers as the typical assistance center, this place had winding lines outside it almost every hour of every day. Desperate people had learned America was open again and they flocked toward the promise of human dignity.

Any time an opponent of the president would demand to know how the U.S. government was going to pay for the assistance centers – derided by racists as Great Replacement Shelters – she would say “justice has no price tag. We will pay what it costs and we will be stronger for it.” I loved her for that. We could afford what we wanted to afford.

The Breaking Of The Man With The Iron Heart

I connected Geoffrey with a family of five: A mother, a father, two little girls, and an older brother. The brother, Victor, was old enough to know what Geoffrey’s tattoos meant. He had seen similar tattoos on the secret police who had imprisoned his family after they made a 400-miles trek across the US-Mexico border. I noticed Victor could not bring himself to so much as look at Geoffrey, and I could not blame him.

I told the family that Geoffrey had been warned that any inappropriate behavior – even a loose comment about the family’s heritage or immigration status – would land him back in the camps. Usually I didn’t use threats to keep prisoners in line, but with Geoffrey and other hardened former police, I was left with little choice. All they understood – for now – was force. I promised Geoffrey I would put him in a cell with the men who had threatened to castrate him in the camp if he had one misstep with his assigned family. He nodded and rubbed his tattoos.

The parents had been eager to have an assistance center worker assigned to their family. Their middle daughter, Maria, had sustained myriad injuries in their journey to the United States and had never been properly treated for her diabetes. She needed physical therapy to fix her left foot, which had never fully healed from breaking it on the family’s trek north. The Brownsville assistance center was at capacity; officials were forced to rotate trips to local hospitals, with many incoming migrants going days without needed care. It was a crisis. We did the best we could. Often it wasn’t enough.

Geoffrey’s job would be to escort Maria to and from the doctor every day for three weeks. She would get her physical therapy and treatment and medication for her diabetes, along with care for whatever else ailed the frail little girl. Over the coming days, I watched and documented Geoffrey’s handling of the girl, who often needed help getting from one appointment to another. Geoffrey dutifully pushed her wheelchair down the hallways of the hospital and worked with hospital staff to coordinate Maria’s treatments and appointments. He seemed resigned to his fate as helper to a family he would have tortured in a previous life. Even when Maria would trade jokes with nurses, Geoffrey was stone-faced and distant. Maria would smirk and call him Mr. G and he had no reaction whatsoever. In the records I filed with the Redo commission, I wrote: “Prisoner 81889 appears detached. He’s doing what he needs to do for now.”

It was a Saturday morning, according to my records from back then, when the hospital was swamped with an influx of migrants who had been wounded by a heavily-armed militia near the southern border – radical anti-Redo forces that had partnered to harass, intimidate, and kill incoming migrants who had heard the president’s welcome message, broadcast on media outlets and social media channels throughout Central and South America. Something that was not widely reported in those rough early days of the Redo: The president authorized the military to drop bombs on the militias’ headquarters and fire as a first resort upon any contact with militia members. Hundreds were killed in government raids, many of them innocent family members of the militia members. She did what had to be done, however messy, however bloody.

Hospital staffers scrambled that Saturday morning to create a makeshift triage underneath a tent outside the emergency room, though the tent offered little protection from the baking Texas sun. I had never seen anything like it – a scene ripped from the bloodiest part of a war movie. It took me a long time and a lot of therapy to move on from that day.

Geoffrey’s reaction was altogether different. He snapped to attention, shifting into a gear I had not seen since being assigned to his case so many months before. With no wheelchairs available for Maria, Geoffrey scooped her up and hustled her to the physical therapy room. I followed close behind, alarmed by his sudden alertness and the speed with which he was operating. Geoffrey set Marian gently on the physical therapist’s table, turned to me, and asked how he could help.

“With what?” I said.

“With the people downstairs,” he said. He asked what had happened, so I shared the scant details of what I had gathered about the deadly attack on the migrant caravan. I think I saw a flash of shame on Geoffrey’s face. He quickly shifted back into his high gear, left the room, and ran down four flights of stairs. I could hardly keep up. Panic swept over me when Geoffrey barged into the triage area outside the ER and I lost track of him in the mass of misery. When I found him – thirty seconds later, an eternity when you’re tracking a dangerous man like Geoffrey – he was helping a nurse carry an elderly man whose legs were riddled with bullets to a nearby gurney.

I watched as the nurse asked Geoffrey to hold the man down while she attached an IV to his arm. The man writhed and yelped in agony, screaming something about his wife. Geoffrey held the man down, looked up to the sky, and mouthed again and again: I’m sorry.

I set down my tablet and did what I could do to help the triage unit in the blistering late summer Brownsville heat. Geoffrey and I carried people, conscious and unconscious, yelling or in silent shock, as ambulances – pockmarked with bullets – roared to the hospital’s entrance. When a young girl who must have been about the age of Geoffrey’s late daughter, Marlene, said to Geoffrey, “Help, help, help,” I saw tears mix with the buckets of sweat pouring off his face. We made fleeting eye contact before he turned away to hide his tears. I didn’t try to hide mine; I cried the entire time. There was so much pain in those early days of the Redo. The younger generations won't remember, but we can never forget.

Hours later – maybe two, maybe four, it was hard to say – the triage area had stabilized. The wails and shouts died down, in part because so many patients had died from blood loss. Geoffrey sat in a shaded area near the ER’s entrance and rubbed the iron cross tattoo on his forearm. It was covered in blood. His face was splattered with other people’s blood. His shirt was ripped and bloody at the bottom. His muscular shoulders were slumped in a way I had not seen. I asked if he was OK. No response. I told him it was time to check on Maria.

We walked up the hospital stairs in silence and entered the physical therapy room, where Maria had been eating cookies and watching a cartoon about teenage unicorns of some sort. She was oblivious to the day’s horrors, and didn’t seem to notice or care about the blood on Geoffrey. “Hi Mr. G,” Maria said in her tiny voice, sweeping aside her long black hair to look up at her caretaker. “Wanna watch with me?”

Geoffrey fell to his knees and let out a shudder of pain and grief and regret that had festered in him for too many years to count. He bawled like a child there in front of Maria. “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” he blubbered. “I’m sorry.” Again I was reduced to tears. It felt so unprofessional, so beneath my status as a Redo coordinator, and yet, so unavoidable. How could I not be touched by the Man With The Iron Heart softening so completely, succumbing to the humanity he had so forcefully repressed over all these years, all through the Bad Times. I watched as a million pounds of pain evaporated from Geoffrey’s massive shoulders all at once. He had been trapped in a cage of his own torment – and his own making – for too long.

Maria slid off her chair, put down her cookie, and hugged Geoffrey. “It’s OK, Mr. G,” she said. “It’s OK.”

Follow Denny Carter on Bluesky at @dennycarter.bsky.social

Comments ()